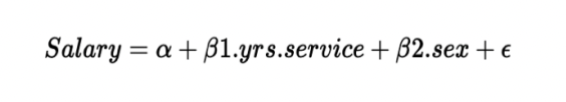

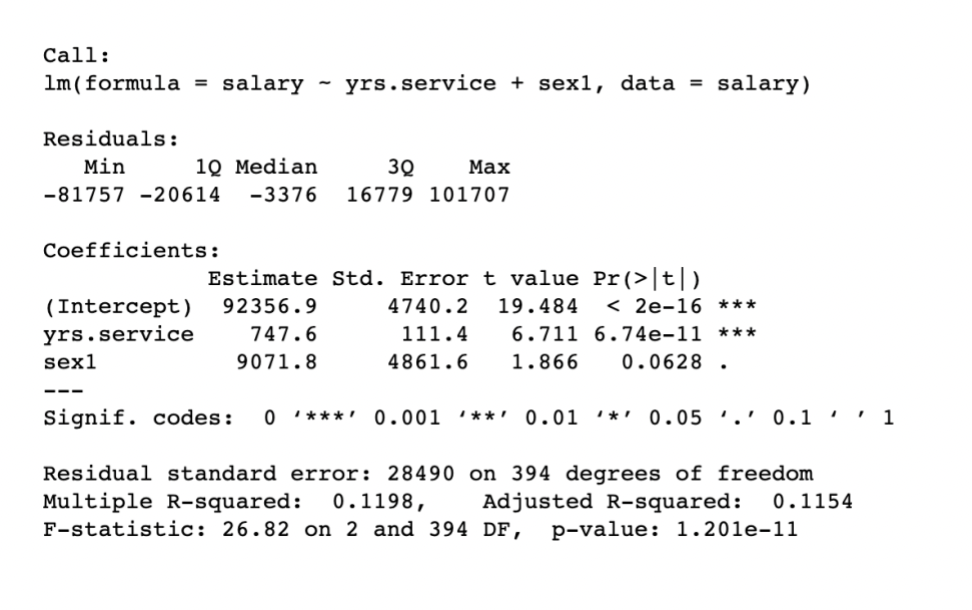

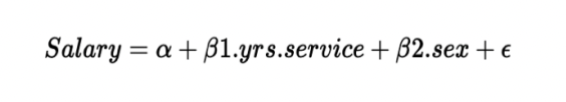

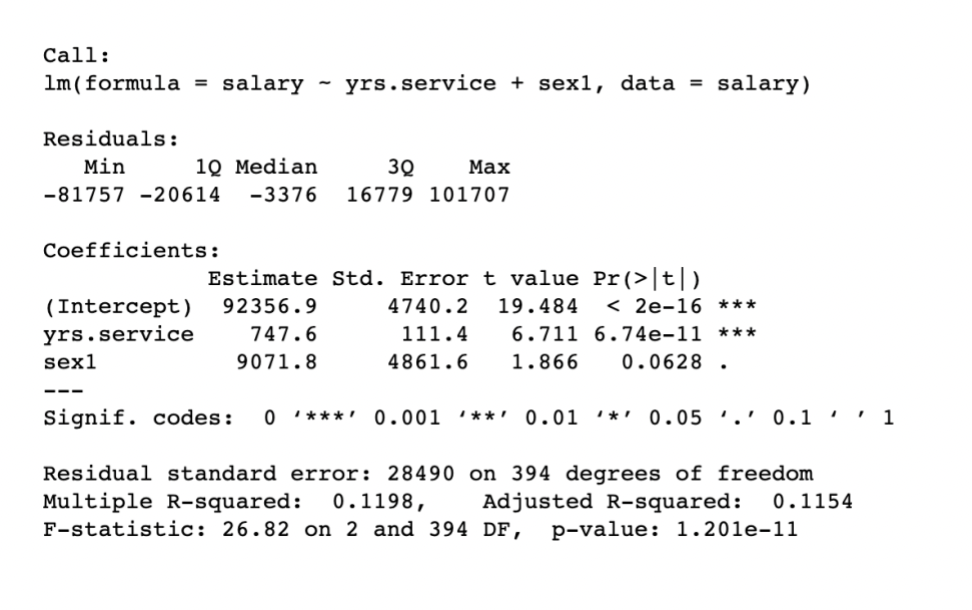

The formula represents a linear regression of salary annually (in US Dollars) based on their years in service and a dummy variable (0-1) depending on the gender of respondents. Based on the intercept, I expect a hypothetical female professor with 0 years of service is 92,356 dollars. The absolute t value is 19.484 (greater than 2); therefore, I can conclude that the test is statistically significant, and the coefficient is significantly different from 0 at 95% of a confidence interval. The years in service coefficient is 747.6; therefore, we can demonstrate that by keeping other factors in the regression constant, gaining one year in service will help the professor's salary increase by 747.6 dollars, and a t-value is 6.7 (greater than 2) that make the test statistically significant. Finally, there is no association of gender in salary, as demonstrated in the t-value is lower than 2, making the test not statistically significant.